Grid defection is unusual — but it may not be for long.

Economic conditions are now favorable for electricity customers to generate their power off grid in five US states: California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Massachusetts, and New York, says a new study by researchers at Western University in Ontario, Canada.

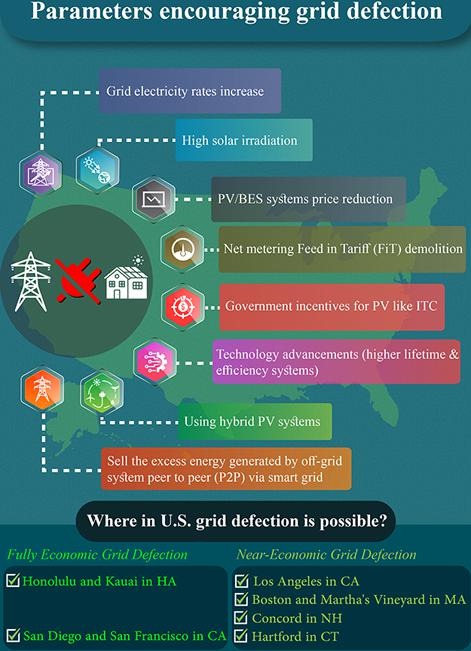

High utility rates, falling solar and battery prices, and unfavorable net metering rules are factors creating “near term” incentives for electricity customers to cut the cord with their utility, according to the study, “The threat of economic grid defection in the U.S. with solar photovoltaic, battery and generator hybrid systems.”

Watch researchers Seyyed Ali Sadat and Joshua Pearce describe their grid defection findings. The first 20 minutes is free to the public. The full one-hour talk, including Q&A with the audience, is available here in the Energy Changemakers Community.

While grid defection is rare, it has been growing — and not just among the off-grid counter-culture. Wineries in California and a large hotel in New York City have defected in recent years, citing high costs and grid interconnection hassles. An upcoming episode of the Energy Changemakers podcast looks at an eco-conscious apartment building in Michigan being built off-grid in an urban setting. (Follow the podcast here or by subscribing to the free Energy Changemakers Newsletter.)

Utility death spiral revisited

Wider-scale grid defection is likely to re-invigorate concerns about the utility death spiral — a term that describes the flight of customers from utilities because of high rates, which in turn causes utilities to raise rates even higher to cover costs, causing additional flight until the utility can no longer sustain itself. Policymakers and utilities worried about this phenomenon a decade ago when distributed energy began to gain traction. But economists largely dismissed grid defection as too technically challenging for consumers. Now falling distributed energy prices and better energy storage may change that calculus.

To some degree, utilities could be bringing the death spiral upon themselves. When they create conditions that make it expensive or hard for customers to install grid-connected solar, they inadvertently incentivize off-grid solar, according to the paper.

“As utility rate structures shift away from net metering, increase unavoidable costs or restrict grid access, solar prosumers have an increasingly economic path to grid defection,” write the paper’s authors, Seyyed Ali Sadat and Joshua Pearce.

Check out our podcast about an urban apartment building being built off grid in Michigan. Follow the Energy Changemakers Podcast.

According to the paper, one problem is that utilities are decreasing net metering compensation for solar customers even though studies indicate that the payment was already too low.

The grid defection findings come at a time when utility rates have been exceeding inflation, and consumer advocates worry they will rise more as utilities take on expensive capital projects to serve growing electric demand.

Where grid defection pays off now

Future rate increases aside, disconnecting from the grid is already economical in the islands of Hawaii and Kauai and the California cities of San Diego and San Francisco. Communities on the margin include Los Angeles, Calif., Boston and Martha’s Vineyard, Mass.; Concord, NH; and Hartford, Conn., according to the paper, which examined grid defection potential at 18 locations across 13 states.

The researchers say that besides economic considerations, the quality of solar irradiation affects the likelihood of grid defection. Longer battery duration also increases the appeal of going off grid.

One caveat. The study looked at hybrid solar plus storage systems containing diesel backup generation. The researchers note that using fossil fuels could discourage off-grid systems in some regions.

Still, the authors conclude: “Overall, the results of this study and the clear trends in economic and technical development indicate that regulators must consider mass economic grid defection of PV-diesel generator-battery systems as a near-term possibility and design rate structures to encourage solar producers to remain on the grid to prevent utility death spirals.”

The researchers add that more study is needed on whether consumers will take the trouble to defect from the grid. Entrepreneurs may solve this problem. The study points to a business model that offers “grid defection as a service,” much like energy as a service or leasing programs. In this model, the business handles installation and operation, taking pressure off the consumer. The business and the customer share savings achieved through grid defection.