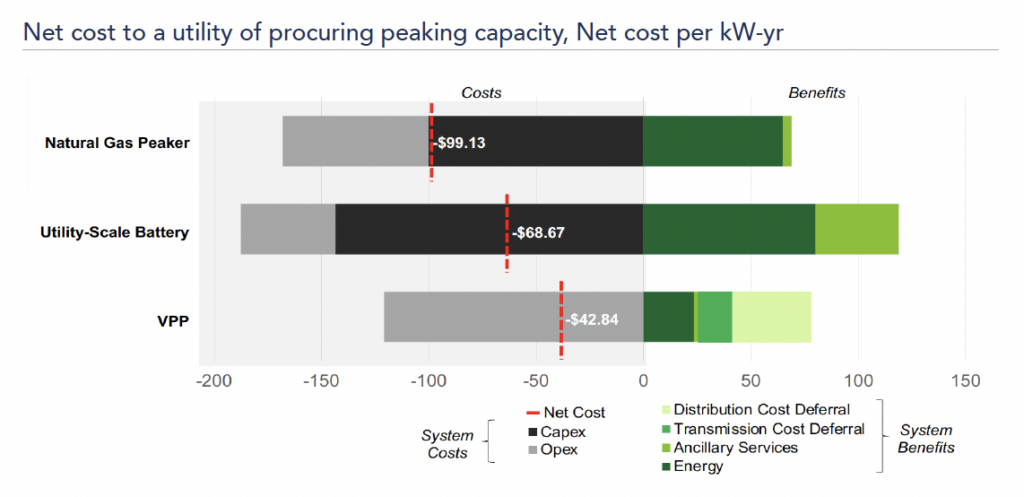

The Department of Energy released a pivotal document in September on virtual power plants (VPPs), a “liftoff” report designed to help commercialize the technology. Highly referenced within the emerging industry, the 74-page report found that deploying 80-160 GW of VPPs by 2030 could avert as much as $10 billion in annual grid costs.

After six months and many conversations with the industry, how does the lead author, Jen Downing, think now about the report and its findings? What would she change? And what should the distributed energy community watch for next from the DOE Loan Programs Office, where Downing serves as senior advisor?

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Downing. Below is an edited version of our conversation. The full interview is available in the Energy Changemakers Community.

Wood: If you were to rewrite the VPP liftoff report today, would you modify, delete or add anything?

Downing: I’m already thinking about novel analyses that we could add or what an update or addendum could look like. Some of the ideas that we’ve had would be a state-by-state analysis of market attractiveness based on utility regulations or wholesale market rules or a deeper dive into the hardware and software configuration, looking under the hood of virtual power plants and exactly how the technology works.

The other thing I think would be interesting would be a comparison across Japan, Germany, the UK, and maybe Australia — what their markets look like and what the US could learn from them.

I can’t think of anything that I would delete, to be honest. I think it all has been pretty well received.

Wood: What are the one or two concerns you hear repeatedly from VPP providers? Are they fixable?

Downing: One big concern or obstacle that I hear about from VPP providers is the lack of long-term certainty about the programs or tariffs that they are building around. For a provider, it takes a lot of upfront investment to build the program, to enroll the customers and to establish an M&V methodology and a definition of the services that are going to be provided, and to structure the incentives for participants. And it’s pretty rare for providers to have a contract with the utility that lasts more than a few years. In different parts of the country, we have wholesale market rules changing as well.

Long-term certainty would really help providers invest nearer term and have more confidence in those investments to build out programs with a longer lifetime.

Now, is that fixable? I think it is, particularly if you think about providers working directly with utilities. It’s fixable by utilities and their regulators (or if it’s a co-op their members; if it’s a muni, their stakeholders.) It’s about doing long-term planning and thinking about VPPs as kind of a critical resource for delivering reliable, affordable, and clean electricity rather than, oh, we’re going to experiment with this. We’re going to see how it works. We’re going to collect some data and then we’ll decide what to do with it.

Wood: That’s very interesting. Two things come to mind immediately. One I hear a lot is: Could the utilities please think about virtual power plans in their integrated resource plans? I imagine that could lead to longer-term planning. Another thing I’ve just recently heard about is a bill proposed by Senator Stern in California that is something like a renewable portfolio standard for virtual power plants.

Downing: There are a lot of different factors that prompt utilities to choose virtual power plants. It’s not always, ‘Hey, we want this much demand flexibility.’ Sometimes it’s we have a priority to have more distributed generation in our state. And to make that more manageable, we need to pair it with a battery and make it dispatchable and ideally get benefits to our distribution system and the bulk power system.

Therefore we need utilities to be bought in.

There’s a couple of different links to the logic chain that help you arrive at virtual power plants. So whether it’s a mandate about demand flexibility similar to an RPS, or it’s about integrating more distributed renewables or it’s just about resilience. I listened to a great podcast with the head of United Power. He was saying one of the positive side effects of the virtual power plant is that they have much more visibility into their distribution system, including their transformers, which means their transformer failure rate is far below the national average — which is obviously super important at this point in time when it’s hard to get new transformers.

Wood: The VPP Liftoff report talks about the need to build utility confidence in VPPs. Can that be done given that there appears to be an inherent disincentive for utilities to support VPPs?

Downing: I want to tease out two separate challenges.

One is having the confidence in the technology. And part of that is just having a good understanding of how the technology performs.

Just having the right analytics to predict how aggregations of heterogeneous DERs will perform — that will build confidence that these are dispatchable resources that are going to show up. And to be clear, you don’t need every single DER to show up when you have tens of thousands in your aggregation.

That’s separate from: Do I have the financial incentive to actually choose that solution even if I had full confidence in how that technology will perform? There are lots of different ways that — if we’re talking about investor-owned utilities — regulators can create this incentive…performance-based regulation, performance-based ratemaking, non-wires alternative requirements, all-source procurement mechanisms.

I don’t think it’s cross our fingers and hope regulators do these things. I think that load growth and the rapid increase in peak demand is a real game changer here because there will need to be more investment in new distribution and bulk power system infrastructure on top of all of the money that we need to spend to maintain and modernize it. And that is going to create upward pressure on rates, and honestly, opportunities for IOUs to make money on those CapEx investments. But the regulators are going to say, this is too much. We cannot approve these rate increases. You’ve got to find a way to save money while delivering on this energy or delivering energy reliably. And so they’re going to look for lower-cost solutions such as virtual power plants.

Wood: So the messaging really has to be — regulators need to understand — that this is a lower-cost approach, a way to dampen rates? Because you do hear utilities sometimes say: “It’s too expensive. It’s too hard to get the customers involved. It’s going to cost a lot of money to do that kind of thing.“

Downing: Yes, and as I mentioned before, there may be other reasons to do this, right? I want more backup power on my distribution grid. I want to integrate more renewables. I have other priorities. But I think cost is just common across everyone and will be more and more urgent given demand growth.

Wood: Some think that virtual power plants are a very complicated approach to bringing more DERs onto the grid and that we should focus more on forming a grid where DERs are not going up into the wholesale market. I’m curious what you think about that.

Downing: Whatever gets us there faster in terms of VPPs delivering value to the grid — because they deliver value both at the distribution system level and the bulk power system level. And there are lots of different mechanisms for realizing that value.

I look at examples like Massachusetts…where virtual power plants can participate in ISO New England and Massachusetts has a clean peak standard that rewards them for doing so, to shape peak so that they don’t have to turn on as many natural gas power plants. Now, Massachusetts has also recognized that we could be getting double the bang for our buck if we do this on constrained circuits on the distribution grid. And so they have a distribution circuit multiplier where you get twice the incentive if you are dropping that load on a constrained circuit. And what they have done is they’ve required utilities to publish basically a map of the 10% most constrained circuits. They publish that so the aggregators can then target the most valuable place on the grid.

So that’s one way, where you can basically do both — get the value both at the bulk power system level and the distribution system level. This is something that we are thinking about at DOE. We’re actually in the process of scoping out new analyses that quantify the benefits, to the bulk power system and separately to the distribution system, of demand flexibility.

You can imagine we need new methodology to run these different electrification and demand flexibility scenarios on a very granular map or model of the distribution system [and] to then model the power flow and how we would need to expand the distribution system. And then assign a dollar value to that and say, Hey, if you can get this much demand flexibility from your EV charging or grid-interactive buildings, it’s going to save you 10% or 20% or 30% in your distribution system cost alone, which translates to savings for ratepayers.

The question about whether we’ll get more value at the distribution system or the bulk power system out of VPPs is not a settled question. And the answer, I think, should be both. And it’s a really complicated optimization problem. So we need people who are very good at math to be mapping this.

Wood: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Downing: it’s been very exciting since the liftoff report came out in September. There has just been so much activity around this both within and outside of DOE.

Within DOE, there’s a lot of foundational work in beginning to develop standards like grid services definitions and aggregator codes of conduct. And we’re working with NAESB on a standardized contract language, really trying to accelerate the maturing of the market. We also have revamped technical assistance for regulators coming out of our Office of Electricity and Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Office. There are demonstration projects happening with more distributed energy systems

So that is all really exciting to see. We’re working in a more coordinated way across the department on these issues because they are so vast.

And then outside of DOE, you look at the market, there’s been M&A activity, which I think suggests people are recognizing the value of this. Companies are transacting to capture the most value out of their respective strengths.

Nonprofits and industry organizations like EPRI, GridWise Alliance, the DER Task Force and the RMI Virtual Power Plant Partnership all have their own work streams going. We show up at the same conferences and talk to each other about our work. I think there’s a growing community that is really effectively working together.

Subscribe to the free Energy Changemakers Newsletter.