After listening to our recent podcast, An Energy Economist on the Abundance Agenda, a listener asked me what specifically could be done to put consumers at the center of energy planning.

Work by the Possibility Lab at the University of California, Berkeley may point in the right direction.

In a recent lab paper, Achieving Energy Abundance: The Role of the Civil Economy and Institutional Diversity, Keith Taylor proposes a form of local energy ownership beyond individual households putting solar on their roofs, or other common strategies like electric cooperatives and community energy.

“Capacity building is more than just an entrepreneur’s access to the grid; it also involves broader engagement of citizens as prosumers and going beyond mere individualized approaches,” Taylor writes. “What if policy incentivized joint action for prosumers much the same way we incentivize joint action for IOFs [investor-owned firms] —e.g., pooling capital to control a firm to develop profit for investors?”

How might this work? Here is an excerpt from the report describing an approach:

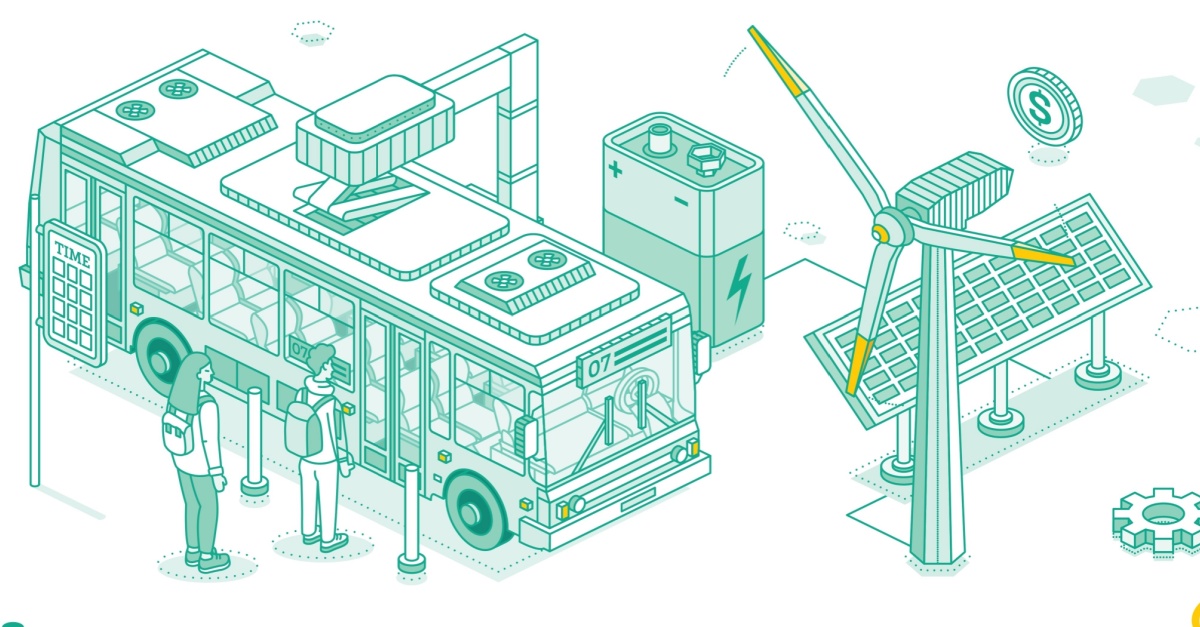

• Instead of managing the entirety of their rooftop solar operations, prosumer homeowners could work through a prosumer-owned company that manages their rooftop solar on their behalf, from maintenance to the business details with the utility

• Once established, renters could buy into the prosumer-owned solar provider, to become a part of the enterprise, thereby creating more public involvement in clean energy supply

• Companies, municipalities, communities, and individuals could build battery storage behind the substation, to store surplus clean electricity when it is most prevalent and deploy locally on an as-needed basis

• Technologies such as virtual power plants (VPPs) can manage these collective resources, reducing the challenges of broad-based participation and managing the dynamism of this system. What is more, VPPs help to harmonize the prosumer’s participation in the grid while reducing the friction of utilities managing distributed energy resources (DERs), thus minimizing opposition from incumbents to procuring power from DERs

“Instead of waiting on the incumbent utility to make significant investments in transmission infrastructure—the middle-mile of the electric grid—innovations can happen locally, behind the substation (at the community or neighborhood level)and behind the meter (at the household level),” Taylor writes

The full paper is available here. Definitely worth a read!