It’s been a tough few weeks for electric vehicles (EVs) following reports by auto executives that demand hasn’t been what they expected.

The news created damning headlines like this one from Business Insider: “Auto execs are coming clean: EVs aren’t working.”

Speculation is running high about the cause of the problem. Some blamed EV costs, others resurrected the range anxiety boogeyman and still others — the EV deniers — are saying, “I told you so.”

None of this seemed right to me. So I contacted Loren McDonald, a market analyst who has been crunching numbers on EVs and EV charging for several years.

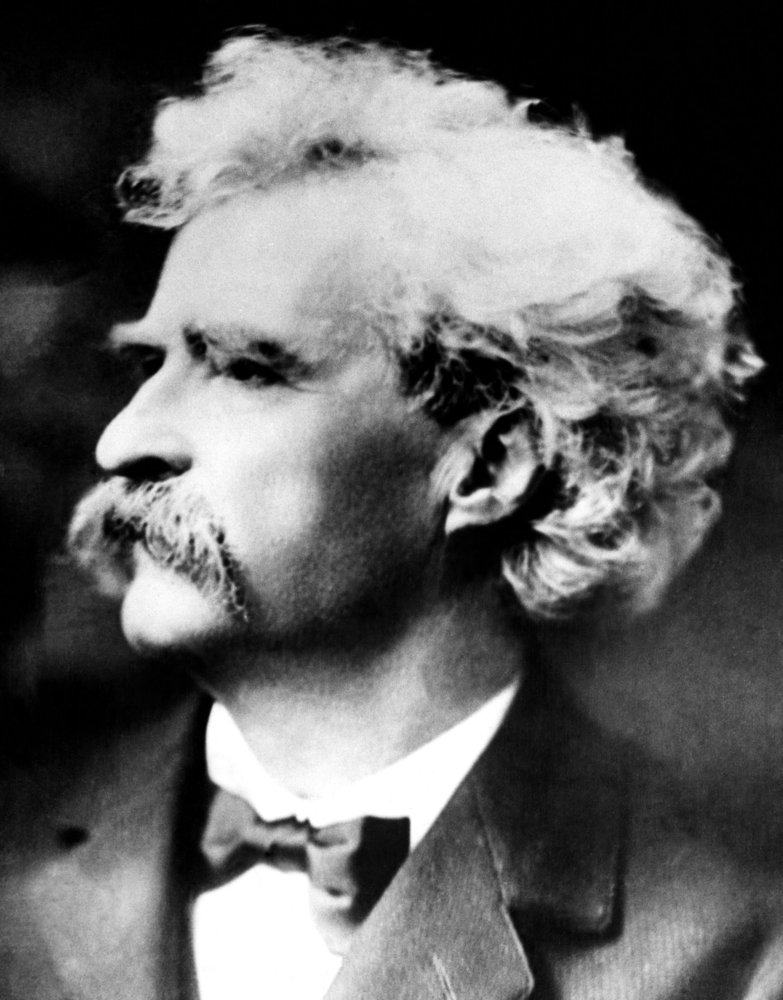

McDonald painted a very different picture, so much so that if EVs were personified, they’d take the form of Mark Twain announcing that reports of his death have been greatly exaggerated. Here are the highlights from our discussion.

First, the issues affecting the EV market are far more nuanced than the simple media refrain that demand is lower than automakers expected. The question should be demand for what, where, and when.

It’s offbase to describe a national market for EVs; more appropriate are state or regional markets. California and North Dakota aren’t even in the same universe when it comes to EVs. In California — the fourth largest economy in the world — zero-emission vehicles account for 25% of new car sales. That’s well over the 16% percent that McDonald estimated would put the EVs “over the chasm,” a term coined by Geoffrey Moore to describe the leap new technology must make to capture the mainstream market. So in California, the EV market has made it. Meanwhile, North Dakota hasn’t yet hit one percent.

Next, while some models are not selling as fast as automakers expected — and a lot of noise is being made about them — other models are experiencing brisk sales. As the auto industry produces more and more models, competition rises, and some do better than others. The Chevrolet Bolt, a moderately priced EV, had a record first quarter and will become the third-largest EV seller this year.

In fact, most EV models experienced growing sales — 31 saw a rise; 12 saw a loss, according to Mcdonald.

And last, it’s important to consider EVs in the broader context of business activity. Genesis saw sales of its three battery electric vehicles drop 7.6% in October. But sales of its internal combustion engine models declined about twice as much.

Much of the bad news focuses on Ford and General Motors, which announced they would pull back on EV production, citing losses and slower-than-expected demand. In truth, their overall EV sales were up 22.9% for Q3 2023 versus Q3 2022. These figures undercut the argument that demand for EVs is faltering, according to Mcdonald.

So what did happen to cause automakers to slow down their EV production plans? Poor planning. Pandemic-era supply chain shortages created waiting lists for EVs. Automakers assumed that demand would continue after production ramped back up, and they set targets accordingly. But the targets were too high because many people didn’t wait around but bought something else, including Teslas that were available, he said.

“There is strong demand. The automakers screwed up. They produced too many EVs,” Mcdonald said.

But we might want to give them a pass. While automakers have decades of experience discerning ICE vehicle demand, they still struggle to understand the patterns of this newer technology. Still, auto leaders should weigh their words carefully about the market. EVs have become victim to the fierce partisan political divide in the US. Any hint of market weakness is likely to be exploited.

To look deeper at Mcdonald’s number crunching, see a series of great posts by him on LinkedIn.

This article was produced by Energy Changemakers, a community for energy professionals advancing the decentralized grid. Join us!