An Interview with Michael Smith, CEO of CPower

Friends have told me that after installing solar and batteries in their homes and businesses, they were eager to take the next step and join a virtual power plant (VPP), only to find none available to them.

So I was struck during a recent conversation with Mike Smith, CEO of Cpower Energy, about the company’s efforts to stretch both the geographic and technological confines to make virtual power plants available to more of us. Smith and I spoke last month during the company’s GridFuture 2024 conference outside Washington, DC in Maryland.

Founded in 2014, CPower was originally known as a demand response company but, in recent years, rose to a top market position for virtual power plants, according to a Wood Mackenzie report. At the time CPower managed 6.3 GW of virtual assets, which this year grew to 6.7 GW across 27,000 sites, the equivalent of about half the summer peak electric demand in Maryland.

A virtual power plant aggregates distributed energy resources (DERs) to serve the grid in return for payment that helps reduce energy costs for the customers that host the DERs. With solar, batteries, EVs and other DERs proliferating, virtual power plants appear to be a technology whose time has arrived.

“We should be able to do this anywhere”

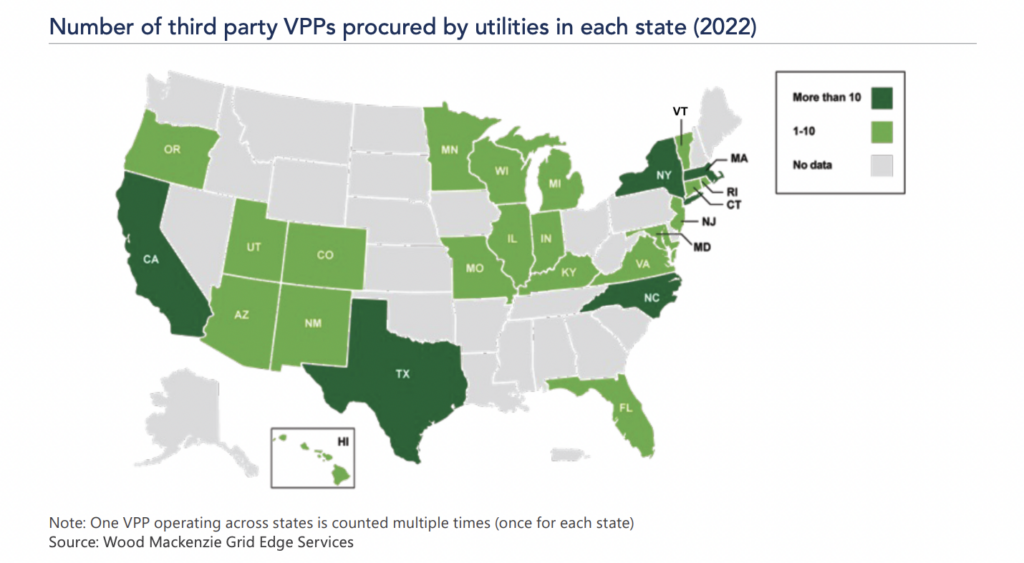

But Smith is frustrated with how difficult, if not impossible, it is to build virtual power plants in several states. VPPs are now concentrated where favorable market rules exist, largely the Northeast, North Carolina, Texas and California.

“Anybody with a building can be in a VPP and we should be valuing this across the country,” said Smith. “We should be able to do this anywhere.”

The company is focusing on making states more virtual power plant friendly, including the toughest cases, the states in the middle of the country that have not restructured their electricity markets.

In comments filed with the Missouri Public Service Commission, CPower said that a number of these states labor under misconceptions about virtual power plants, some perpetuated by those “motivated by a desire to restrict competition and maintain a protected market for demand side services.”

One misconception is that virtual power plants should be subject to utility regulations. This doesn’t make sense, CPower argued, because virtual power plants are not natural monopolies like utilities.

CPower and other VPP advocates won their case when the MIssouri commission issued an order in October 2023 that for the first time allows businesses in the state to join virtual power plants to provide demand response in wholesale markets.(File No. EW-2021-0267).

Interested in virtual power plants?

Subscribe to the Energy Changemakers Newsletter.

But that’s just one win. Ultimately, what’s needed are standard rules for virtual power plants across all states, according to Kenneth Schisler, CPower’s senior vice president of regulatory and government affairs.

“If you have a thousand flowers blooming — a thousand different products — innovators can’t craft their solutions to meet the requirements of all one thousand,” Schisler said.

So educating the states has become a key task of CPower’s regulatory team. It’s a slow process. Retail power is governed at the state, not the federal level. There is no one-stop fix.

Expanding the customer base for virtual power plants

Expanding virtual power plants isn’t just about geography but also broadening the customer base. For CPower this means reaching beyond its commercial and industrial customers into the residential market.

“The biggest opportunity in VPP space is in the residential, small space, these really tiny loads like nest thermostats,” Smith said. “Getting to that piece of the market is really going to be very important for us collectively as an industry.”

Residential VPPs are challenging because they require sophisticated automation and participation by the grid operators and the utilities, who will need to recognize smaller load profiles, he said. “There is a lot of work being done in that space right now.” CPower is putting a toe in that market in partnership with a residential aggregator of Nest thermostats, an endeavor that Smith described as “experimental.”

Energy insiders continue to mull just how much interest households will take in all of this. While early adopters, like my friends, are frustrated that they can’t find virtual power plants, most people don’t think about energy much, so they may not be apt to sign up.

But Smith said he believes residential customers will participate if they are shown the value, especially if automation makes virtual power plant participation easy — and if they hear about it from friends and neighbors.

“It’s kind of like how solar rolled out. One house on the street gets solar. They talk about it at the local happy hour and pretty soon the whole street’s got solar,” he said.

So to my friends who wish to join a virtual power plant. Hang in there. They’re coming. It just might take a while, depending on where you live.